It’s important to note that the following article does not claim or attempt to claim that FreeDomain Radio is a destructive cult. It presents information on destructive cults in general and examines some of the public, documented, and controversial aspects of FreeDomain Radio. It’s up to you to draw your own conclusions.

Part 1:

How can you tell if it’s a cult?

Whenever a group appears to enjoy a high degree of devotion from its members, the question inevitably comes up: is it a cult?

When I got my first glimpse of the dark side of Stefan Molyneux’s FreeDomain Radio, it’s the first question I asked.

Since then, I participated in lots of conversations and had changing viewpoints over time. Over a year ago, I was arguing that no, FDR is not a cult and Stefan Molyneux is not an evil cult leader. For most of the writing I’ve done so far on FDR Liberated, I’ve left the question up in the air.

Then I realized why I had changing viewpoints and why so many of the “is it a cult” conversations regarding any suspected group lead nowhere.

I didn’t know anything about destructive cults. And neither did virtually any of the people I was talking to.

So I educated myself, starting with the seminal book Cults in our Midst by Margaret Singer. I read quite a few others and in time met and conversed with two cult extraction experts.

The word in search of a definition

It didn’t take long before I began to understand why nearly every argument about whether FreeDomain Radio (or any other suspected group) is a cult almost immediately detours and founders on the question what is a cult?

Most often, someone will try to answer the What is a cult? question with a list of criteria from FactNet.org or some similar place and then begin checking each criterion against their impression of FDR. Stefan Molyneux himself has done that on several occasions to argue his innocence. One was a video originally uploaded to YouTube but since made private for reasons unknown. The audio-only podcast is still available, however.)

Those lists have their place, especially as general “warning signs” for those who are uneducated about cults. But they are not always useful as definitive tests. For starters, there are so many different types of cults, the lists allow for a great deal of subjectivity. And quite often, people will take advantage of that subjectivity when trying to claim such lists “prove” or “disprove” that the group in question is a cult.

As a result, I noticed that most on-line discussions soon devolve into the “therefore, anything could be called a cult” position vs. 27 other interpretations.

One person will eventually try to convince everyone that all families are cults (Actually, that is another Molyneux belief!). Another will try to make the pithy observation that what starts as a cult often becomes our culture. And then the conversation will peter out altogether.

All of that is a wonderful waste of time, but rarely gets us to anything we can take away.

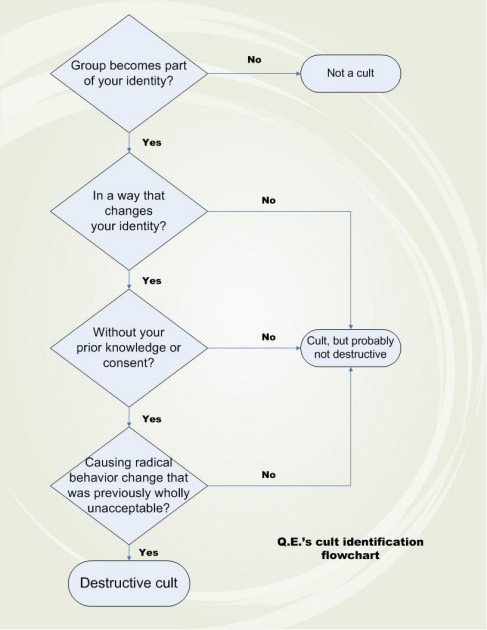

So, what better way to clarify matters than by lending yet another definition to the chatter? Mine isn’t a checklist though; it’s a flowchart! The first three decisions you have to make are about identity and the last one about behavior.

The big difference between my little flowchart and a typical checklist is there’s no cheating allowed and (I think) very little subjectivity. You must go through each step top to bottom and the answer to each question must be yes.

The Q.E. cult-identification flowchart

Right out of the gate, my flowchart (and I) make the assumption that there are these things called cults but the vast majority of them are benign. However, there’s a tiny subset of groups among them that are destructive to those who join. My flowchart is designed to help identify those.

The decison steps in working through the flowchart follow.

Here are the decision steps:

1. Is it a group that becomes part of your identity? This covers a pretty broad territory. Any group you join that defines your identity to any degree can probably be called a cult. By that definition, is FreeDomain Radio a cult? Emphatically, yes. Then again, so are the Chicago Bears, the marines, people who have every book Stephen King has ever written, Methodists, and devoted Jonas Brothers fans.

But usually, when people start throwing around the C word, they’re really talking about destructive cults. None of those other groups mentioned above are necessarily destructive (although the jury’s out on being a Jonas Brothers fan) and in fact can be fun, if not fulfilling. (People who know me can’t imagine I would define either the marines or Methodists as fulfilling, but I’m not making value judgments right now!)

So, if we buy that argument, what’s the next step that will bring the destructive cults into focus? Let’s drill further down on belief and identity. The next question I would ask is this:

2. Does participation in that group actually change your identity? Even this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Some people join certain cults because they specifically intend to change something about their identity and they are seeking the cult’s assistance in doing so. For example, this is often the goal of someone joining the Methodist denomination to lead a “God-centered” life or someone leaving the church in which they were raised to join, say, American Atheists and lead a science- and reason-centered life. When people who can’t stop drinking want to make a change, they often join Alcoholics Anonymous (even though the effectiveness of that group is unclear).

And there are various businesses who conduct what is known as Large Group Awareness Training (LGAT). (I believe the Landmark Forum is one of the better-known examples.) You pay to spend a weekend or so trapped in a big room with a bunch of other students/customers and the leaders use techniques that may be very close to brainwashing to give you a new sense of self-awareness and your of own potential. For all I know, LGATs might be very effective and, if so, would be another benign example of a cult that changes your identity yet does so in a way that participants anticipate and desire from the outset.

We could debate the military endlessly, I suppose. I don’t know if the typical 18-year-old knows exactly what he’s getting into when he joins America’s Fighting Forces in the hope that “it will make a man out of him.” However (setting any battle-related trauma aside), I don’t know if one can determine what kind of role, if any, military training actually plays in changing one’s identity.

My general, empirical observation is that people come out pretty much the same as they go in, a little more fit and with a few more life experiences to draw upon. For many of them, military service was simply a stepping stone to a career they actually desired in the civilian world. Of course, there are disastrous exceptions, but I haven’t seen enough of them to change my point of view that modern military service generally doesn’t change one’s identity and therefore fails at the second decision step. However, we’ll touch on the military again later.

So, we have the set of all groups that become part of one’s identity and within that the subset of groups that change one’s identity. Is there an even smaller subset inside those two that can sharpen our focus further? I think there is.

3. Does the group change your identity without your knowledge or consent? Now we’re getting to the good stuff. As I think about this subset, there are some pretty murky elements in there, but again they’re not necessarily bad. For example, assume you’ve decided as an unmarried student to become an atheist and join an atheist group run by other college students. It is possible that a few years later you will be married with children and find yourself embroiled in a years-long fight to keep your children from being institutionally indoctrinated toward religion in one way or another. It’s a fight that you probably didn’t think about when you started this journey (prior knowledge) or one that you would have preferred to avoid altogether (or consent), but it is part and parcel of your new identity.

Considering that scenario and other similar examples, I think it can be reasonably argued that some groups who meet all three of the above criteria are not necessarily destructive cults. Although one may not have entirely anticipated that the path that began with their “I don’t believe in a Higher Power“-identity would one day lead to “I must fight the institutions that intend to indoctrinate my child“-identity, the progression of beliefs and behaviors seems reasonable. Would these “surprise” identify changes—had one known about them beforehand—have been enough to stop an individual from joining a group in the first place? In instances such as these, I don’t think so.

But I think there is another subset, this time defined by behavior change, that is empirically unreasonable. And it is at this point (and only at this point) that I would ask my final question:

4. Does the group radically change your behavior in a way that would have been wholly unacceptable beforehand?.

Bingo. If the answer is “yes,” then Houston, we have a problem.

It’s not how, when, or why—it’s “would you?”

This last decision in my flowchart helps me understand if a group fits into that tiny subset of destructive cults. It’s why I can avoid (for now) the specifics of how, when, or why cults work or how one particular cult works. If (AND ONLY IF) you’ve answered the first three criteria positively, the one remaining question is this: “is there any possible way you would have chosen beforehand the activities you’re engaged in right now?”

Yes, people may join a mainstream religion and begin volunteering every other week to work in a soup kitchen or atheists unexpectedly find themselves staring down a well-meaning schoolteacher over the school’s Christmas pageant. While they may have found themselves in those positions without their prior knowledge or consent, I believe they still would have accepted the identity change even if they had known about these possible consequences.

But, if you were to ask any sane person the following question, how would they respond? “If someone asks you to forsake your family and friends, lived crammed into a lousy apartment with people you might think are a little scary today, spend your days on the street in dirty clothes handing out leaflets and begging for money, and your evenings in hours-long prayer and chant sessions, would you do it?”

Most sane people would say “Oh, hell no!” Yet that is the behavior change that someone in a destructive religious cult, such as the “Moonies,” might experience. The slippery problem is that if you ask a Moonie that question after their identity conversion within the destructive cult is complete, they wouldn’t be able to respond truthfully. Remember, part of the identity change means that the radical new behavior—no matter how destructive—somehow makes sense to group member.

So it is up to the rest of us to ask ourselves this question:

“Is there any conceivable way this person’s previous identity would have freely chosen the one they have now?”

It’s very important that you don’t jump to that question about radical behavior change until you’ve satisfied the previous steps in the flowchart. Radical behavior changes can and do happen for a variety of reasons. But if all the previous answers on the flowchart are “yes,” then there’s probably only one reason for the behavior you’re witnessing now.

You are most assuredly dealing with a destructive cult.

Extreme conversions

Does this flowchart cover all aspects of destructive cults? No. However, I do have a few thoughts on some extreme examples.

The flowchart is unrevealing when applied to someone with the extreme misfortune of being born into a destructive cult. But that’s where logic can save the day. To the extent that the cult in question recruits new members, we can apply the flowchart to them. Once a cult is identified as a destructive cult, it is equally destructive (perhaps more so) for those born into it.

Okay, but what about someone who joins a so-called “mainstream” religion and within a year or so finds him/herself working in a mission in Africa? Why is that an acceptable behavior change, while begging for donations in an airport is not?

I think the answer lies at the “prior knowledge” and “consent” decision. If one has joined a legitimate religion, then at no time will any effort be made to hide either that some members participate in missions or any task/event that occurs at those missions. In a destructive cult, people are conditioned to accept radical behavior change step-by-step, in the hope they will undergo behaviors or projects on behalf of or under the coercion of the group later on. In a legitimate religion, new members might hear on their first day about the mission work some members do. There are no secret behaviors or projects in a legitimate religion.

Far more important, in a legitimate religion, it won’t change your standing in the church or the perception of your religiosity whether you participate in the mission or not. In a destructive cult, participation in many tasks is mandatory. Failing to comply means at minimum being identified as “still corrupt” and at worst being ejected from the group. That pressure to comply—at the risk of falling in your standing within the group—impairs your ability to consent freely.

Okay, so what about the loss of friends during a religious conversion/de-conversion? Why is it OK to lose friends when you join (or leave) a church, but not OK to discard your friends because you’re involved in so-called “destructive cult”? Neither mainstream religions or mainstream atheists insist that you reject friends (or family), but once an identify conversion occurs, it sometimes happens that friends with formerly shared interests drift way. That’s not nearly the same as an organization that claims family and friends are those who “Satan works through” (as the Moonies often preach) or are “suppressive persons” (as Scientologists often claim)—and insists you discard them altogether.

So, the flowchart doesn’t cover everything, but for me it covers a lot.

What starts as cult…

Before we jump to the next part of this article, I want to address a couple of points that always come up in “cult” conversations. The first one tends to suggest an overall benign nature of cults by saying “what starts as a cult ends as culture.” The underlying argument is that we tend to brand as a cult anything that is outside of the mainstream norm. In other words, so the argument goes, there isn’t much difference between Scientologists and Methodists. We just don’t use the “cult” terminology on Methodists because it is an accepted mainstream religion. And should Scientology one day gain enough traction to reach the tipping point in membership (whatever that may be), it would become mainstream.

I would say that argument is half-right. What starts as cult does often end as culture. That is partly because the majority of cults—including all the ones that become mainstream—are non-destructive.

Yes, according to my flow chart, both Methodists and Scientologists are cult members. But I would also argue that because of the alleged destructive nature of Scientology, it may never become mainstream as it stands today. In my view, it falls through the flowchart all the way to the bottom. We can bring up a few historical examples that appear to be both mainstream and destructive—Nazism, for example—but I don’t think most of these suggestions withstand a lot of scrutiny. My general flowchart still seems to work pretty well for me.

Families as cults

This argument is both a little harder and more important to discuss, since Molyneux himself tends to claim that there is such a thing as a “cult of family.” There are two reasons why I find the argument not worth pursuing.

The first is the intrinsic evolutionary relationship between the family and the biological development of the brain. My view is that there is some kind of evolutionary reciprocity between the two. The human species appears to be born with less instinct than any other species and therefore takes far longer to learn the behaviors it needs to survive. The trade-off is that humans do not become prisoners to instinct and are able to apply nearly limitless inventiveness in developing our skills. For our brains to evolve in this way, we needed a caretaking structure to get us through our helpless years while learning those skills.

That structure is the family.

That’s also why I think of it as reciprocal—the brain and the family structure as we commonly recognize it developed in tandem, and developed each other.

For Molyneux, who appears fond of tinkering with self-detonating arguments, I would say that the family structure whose validity he questions created the brain that made it possible for him to question the validity of family structure. Resolve that one, Mr. Molyneux, and win the million-dollar prize!

That’s the first reason I don’t find it worthwhile to pursue the argument at all. Because of the intrinsic relationship between family and the evolutionary development of the brain, it’s no more illuminating to put “family” on the list of “cults” any more than it is to put “oxygen” on a list of “addictive substances.”

My second reason for discounting the family-as-cult argument has to do with adolescent psychology. Underneath the “families are cults” argument is a view that parents create little automaton versions of themselves that they ultimately unleash upon the world to replicate the parent’s lives. Molyneux’s writings and podcasts suggest he shares this view.

The problem is, if there is one human behavioral instinct I believe in more than any other (after self-preservation and reproduction) it is in the rebellion that manifests during the years of individuation. There’s a lot more of The Wild One (“What are you rebelling against?” “Whaddya got?”) than R2-D2 in adolescents.

According to wikipedia’s entry on Adolescent Psychology, this period of time that roughly stretches between ages 10 and 20 is far different than most “family-as-cult” thinkers would have you believe:

The social behavior of mammals changes as they enter adolescence. In humans, adolescents typically increase the amount of time spent with their peers. Nearly eight hours are usually spent communicating with others, but only eight percent of this time is spent talking to adults. Adolescents report that they are far happier spending time with similarly aged peers as compared to adults. Consequently, conflict between adolescents and their parents increase at this time as adolescents strive to create a separation and sense of independence. These interactions are not always positive; peer pressure is very prevalent during adolescence, leading to increases in cheating and misdemeanor crime. Young adolescents are particularly susceptible to conforming to the behavior of their peers.

Watch almost any movie, TV Show, Facebook page, etc., and you will see almost instinctive rebellion occur during those in the adolescent years. Go back in history as far as you like and you’ll find writers like the Greek poet Hesiod in 700 BC:

I see no hope for the future of our people if they are dependent on the frivolous youth of today, for certainly all youth are reckless beyond words. When I was a boy, we were taught to be discrete and respectful of elders, but the present youth are exceedingly wise and impatient of restraint.

Families seem to me to be designed to eject young adults and the young adults themselves are all-too-willing to reject their parents. I think this is all as it should be and absolutely nothing like a cult.

As an aside, this is one of the reasons why I say that Molyneux didn’t invent adolescent rebellion against parents as he sometimes appears to think—he simply capitalizes on it. I’m surprised more people don’t find it concerning that Molyneux takes the personal approach he does with younger adults. He catches them at the point of individuation, making pronouncements about their families without talking to anyone except his intended target. He not only agrees with any negative, rebellious sentiments they have, he inflames them.

What makes him unique is that he is the only adult I can think of off-hand, outside of Pinocchio’s Honest John, to befriend a young person at the point of individuation with an “every negative thing you feel about your parents is absolutely right!” message.

What makes him unique is that he is the only adult I can think of off-hand, outside of Pinocchio’s Honest John, to befriend a young person at the point of individuation with an “every negative thing you feel about your parents is absolutely right!” message.

So, no, I don’t view families as cults for that second reason, either. If they were—and adolescents truly were little automaton versions of their parents—then actual destructive cults would be almost non-existent!

Addendum

Some who have read the above article have let me know I did a pretty lousy job of explaining myself on the “Without your prior knowledge and consent” decision in my flowchart. In my clumsy way, I was trying to say that in some situations, giving your consent to participate in a cult doesn’t necessarily mean you’re exercising free will in the way we normally understand it—in other words, that it is you who are making the choices.

It’s an important point, so I need to explain it well before we move on to Part 2.

This is it in a nutshell: When you don’t fully know the cult’s agenda, your ability to give true consent is compromised.

This is it in a nutshell: When you don’t fully know the cult’s agenda, your ability to give true consent is compromised.

You can exercise your free will and consent to the agenda as you know it, but if the cult also accepts that as an agreement to the rest of its agenda—the “secret” knowledge it doesn’t share with outsiders or newest members—the potential now exists for a cult to change your identity later in a way you didn’t desire without your prior knowledge or consent.

In typical destructive cults, that information is being withheld specifically because it is something you’d be unlikely to agree to in the early stages of your involvement.

Consider this example:

Suppose a woman has decided that she has led a life of sin and wants to change her ways. So she sees this little church not too far from where she lives—a small church with a lone minister.

She meets with the minister and says she is ready to embrace Christ and change her ways. The minister says “that’s wonderful my child, are you ready to embrace all of His teachings? Are you ready to renounce Satan? Are you ready to change all of your past ways? Are you ready to do what you need to purify yourself in the eyes of the Lord?”

“Yes, yes, yes, to all of that,” she replies. And so she begins down the path to her reclamation. What she doesn’t know is this particular minister believes he talks to God directly. And God has told the minister that the way for a fallen woman to purify herself is through a “union” with a man of God.

But the minister knows she’s not ready to hear that yet, because she’s so “corrupt.” So he has to begin the process of elevating his status with her as a man of God and “work with her” until she completely embraces the guilt and shame of her past life. If all goes well, in a few months she’ll become one more member of the flock that he has had sex with.

I wish I completely made that up, but that sort of thing happens. The point is, the woman had no prior knowledge that she was a sexual target when she consented to “purify herself.” As a result, her ability to freely consent was compromised..

But…if the minister had said at the outset—“first, we need to do a little purification, and it starts with you and me doing the horizontal mambo. Wait here while I get my chaps”? (He’s a pretty weird minister, that one.)

If he had done that, she would have known to give him a good kick in the yarbles and move on.

For this reason, I have a very healthy suspicion about any group that has “secret knowledge” that you must acquire over time. All too often, the path on that journey is seeded with hidden agendas.

We’ll revisit this issue later in Part 2.

Ok, this seems like a good place to take a break for now. If you buy the argument so far, I think I’ve got a fairly productive way to identify destructive cults and among all other possible groups. In Part Two, I focus on the mechanics of identity and behavior change—and maybe then we’ll be ready to make an observation or two about FDR.

Click below to e-mail or DIGG, etc., this article! As always, I welcome your comments!